Over the past two decades, India has made significant strides in bringing fugitives back to face justice, showcasing its growing diplomatic clout and commitment to tackling cross-border crime. From terrorism to financial scams, the country has secured the extradition of several high-profile individuals, with cases like that of Tahawwur Rana, accused in the 2008 Mumbai attacks, grabbing global attention. This article dives into some of India’s most notable extraditions since 2005, explores the treaties enabling these efforts, and highlights the legal frameworks that make them possible—all while maintaining a balanced and accurate perspective.

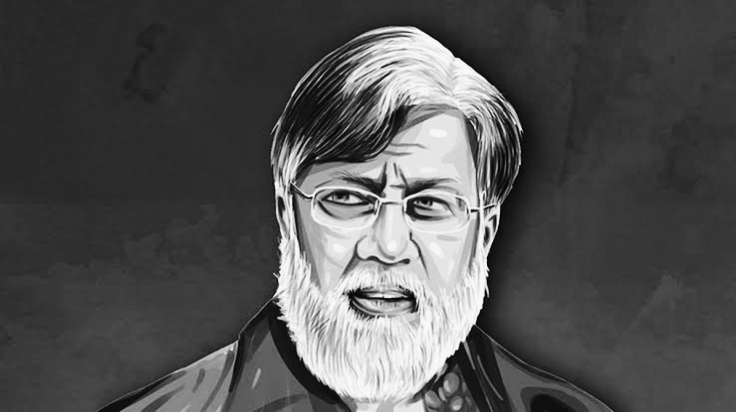

Tahawwur Rana: A Milestone in Counter-Terrorism

In a landmark development, Tahawwur Rana, a key figure linked to the 26/11 Mumbai terror attacks, was recently extradited to India from the United States. The U.S. Supreme Court rejected his plea to block the move, dismissing claims that his life would be at risk in India. Rana’s return to Delhi marks a significant win for India’s pursuit of justice in one of the deadliest terror attacks in its history, which claimed 166 lives. His extradition underscores the strength of India-U.S. cooperation, governed by the 1997 Extradition Treaty, which facilitates the transfer of fugitives accused of serious crimes like terrorism.

Rana’s case is just one of many. Since January 2019, India has successfully brought back 23 individuals to face trial for offenses ranging from organized crime to economic fraud. Let’s explore some of the most prominent extraditions over the past 20 years and the diplomatic mechanisms that made them possible.

Ravi Pujari: From Senegal to Bengaluru

Ravi Pujari, a notorious gangster, was extradited from Senegal in February 2020 to face a slew of criminal charges across India. Once a feared name in the underworld, Pujari was accused of orchestrating crimes like extortion, murder, and arms trafficking. Among the cases tied to him was the 2001 killing of Bengaluru businessman Subbaraju, though a sessions court acquitted him in that matter due to insufficient evidence. The case also involved another gangster, Muthappa Rai, who was acquitted earlier and passed away in 2020.

Pujari’s extradition was unique because India and Senegal lack a bilateral extradition treaty. Instead, the process was facilitated under the United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime (UNCTOC), adopted in 2000. This international framework allows countries to cooperate on tackling organized crime, proving instrumental in bringing Pujari back to face justice.

Rajiv Saxena: The AgustaWestland Middleman

The ₹3,600 crore AgustaWestland VVIP chopper scam, involving alleged kickbacks in a helicopter deal, brought Rajiv Saxena into the spotlight. A Dubai-based businessman, Saxena was extradited to India from the United Arab Emirates in January 2019. Initially, he turned approver, promising full cooperation with the Enforcement Directorate (ED) in exchange for a conditional pardon. However, the ED later accused him of withholding information, leading to further legal battles. In 2021, Saxena faced arrest again in a separate ₹354 crore bank loan fraud case tied to Moser Baer and the Central Bank of India.

Saxena’s extradition was made possible through the India-UAE Extradition Treaty, signed in 1999. This agreement outlines clear protocols for transferring fugitives, ensuring both nations can address serious financial crimes effectively.

Christian James Michel: A Complex Bail Saga

Another figure linked to the AgustaWestland scandal, British national Christian James Michel, was extradited from Dubai to India in December 2018. Accused of funneling €30 million (approximately ₹225 crore) in kickbacks to influence the chopper deal, Michel faced probes by both the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) and the ED. After spending over six years in Tihar Jail, he was granted bail in 2025—first by the Supreme Court in February and then by the Delhi High Court in March. However, Michel raised concerns about his safety, calling Delhi a “larger prison” and expressing reluctance to accept bail unless allowed to leave India. The courts, unmoved, imposed strict conditions, including travel restrictions and a ban on media interactions.

Like Saxena, Michel’s extradition was governed by the 1999 India-UAE Extradition Treaty, highlighting the UAE’s role as a key partner in India’s fight against financial misconduct.

Jagtar Singh Tara: A Decade on the Run

Jagtar Singh Tara, convicted in the 1995 assassination of former Punjab Chief Minister Beant Singh, represents a case of persistence. Arrested soon after the killing, Tara made headlines in 2004 when he escaped Chandigarh’s Burail prison through a 104-foot tunnel alongside three others. He evaded capture for over a decade, only to be rearrested in Thailand in January 2015. Since then, Tara has been held in a high-security cell under constant surveillance. In a rare moment of leniency, he was granted custody parole in 2025 to attend his brother’s bhog ceremony in Ropar, Punjab, under heavy police escort.

Tara’s extradition from Thailand relied on an arrangement established in 1982, as the formal India-Thailand Extradition Treaty, signed in 2013, was not yet in effect at the time. This case highlights how historical agreements can bridge gaps when newer treaties are still in progress.

Abu Salem: The 1993 Mumbai Blasts Accused

Perhaps the most high-profile extradition in this list, Abu Salem, a close aide of underworld don Dawood Ibrahim, was brought back to India from Portugal in 2005 alongside his companion, Monica Bedi. A key accused in the 1993 Mumbai serial blasts, which killed 257 people, Salem also faced charges of extortion and murder. His extradition came with strict conditions: India assured Portugal he would not face the death penalty or life imprisonment beyond 25 years, aligning with Portuguese legal standards. Salem has since been convicted in multiple cases and is serving a life sentence, though debates over the terms of his extradition continue.

The India-Portugal Extradition Treaty governed Salem’s return, showcasing how diplomatic assurances can navigate differences in legal systems to secure justice.

India’s Extradition Framework: A Global Network

India’s ability to secure these extraditions stems from its robust network of treaties and arrangements. Currently, India has extradition treaties with 48 countries, including the United States, UAE, Thailand, and Portugal, among others. Additionally, it maintains extradition arrangements with 12 other nations, offering flexibility in cases where formal treaties are absent.

A notable exception exists with Italy and Croatia, where India’s extradition agreements are limited to crimes involving illicit trafficking in narcotics and psychotropic substances. This restriction aligns with the 1988 UN Convention against Illicit Traffic in Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances, to which all three countries are signatories. Such specialized agreements demonstrate India’s commitment to addressing specific global challenges like drug trafficking.

Beyond bilateral treaties, international frameworks like the UNCTOC play a critical role, as seen in Ravi Pujari’s case. These conventions enable cooperation even with countries outside India’s formal treaty network, ensuring fugitives have fewer places to hide.

While India’s extradition successes are commendable, challenges persist. Legal hurdles, differing judicial standards, and concerns over human rights often complicate negotiations. For instance, Tahawwur Rana’s prolonged battle in U.S. courts delayed his extradition, while Abu Salem’s case sparked debates over sentencing limits. Additionally, high-profile fugitives like Vijay Mallya and Nirav Modi, still abroad, highlight the complexities of navigating foreign legal systems.

Looking ahead, India continues to strengthen its extradition framework, forging new treaties and refining existing ones. The country’s proactive stance sends a clear message: no matter where fugitives flee, justice will pursue them relentlessly.

From Tahawwur Rana to Abu Salem, India’s extradition efforts over the past 20 years reflect its determination to uphold the rule of law. Backed by a network of 48 treaties, 12 arrangements, and international conventions, the country has brought back fugitives accused of terrorism, financial fraud, and organized crime. Each case—whether facilitated by the India-UAE treaty, the UNCTOC, or assurances under Portuguese law—tells a story of persistence, diplomacy, and justice. As India continues to expand its global partnerships, its ability to hold wrongdoers accountable will only grow stronger, ensuring safer communities and a fairer world.