Special Political Report: On a humid morning in July 1987, the Indian Prime Minister’s residence at 7, Race Course Road welcomed an unusual and controversial guest. Dressed in military fatigues, with a steely gaze and few words, Velupillai Prabhakaran, the elusive leader of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), had stepped onto Indian soil not as a fugitive but as a pivotal figure in a regional peace process.

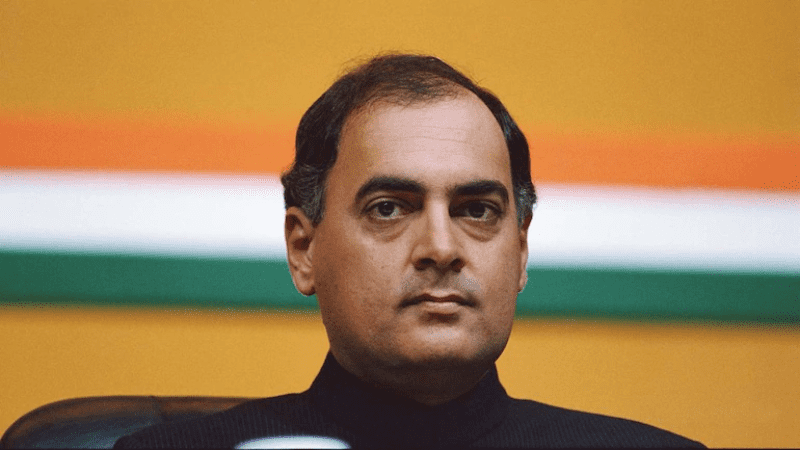

Waiting to meet him was Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi, then just 42, carrying the heavy burden of foreign policy in a volatile neighbourhood. Their meeting, brief and tense, symbolized a rare moment of political hope. According to senior officials who witnessed that encounter, Rajiv offered Prabhakaran a bulletproof vest, telling him to “take care of yourself.” The gesture was symbolic—an extension of goodwill from a statesman who still believed diplomacy could contain militancy.

Four years later, on May 21, 1991, Prabhakaran’s operatives assassinated Rajiv Gandhi in a suicide bombing in Sriperumbudur, Tamil Nadu, marking one of the darkest days in India’s democratic history.

The Indo-Sri Lanka Accord: An Experiment in Diplomacy

The roots of this tragic fallout lay in the Indo-Sri Lanka Accord, signed a day after their meeting. Rajiv Gandhi, eager to solve the ethnic crisis plaguing India’s southern neighbour, believed the accord would ensure a peaceful resolution. It promised autonomy to Tamil-majority areas in Sri Lanka, in return for the disarming of militant groups like the LTTE.

Under this agreement, India deployed the Indian Peace Keeping Force (IPKF) to monitor and assist the transition. But in a cruel twist, the very group India had once supported—the LTTE—turned against it.

Prabhakaran, who had risen from the dusty streets of Jaffna to become the face of Tamil militancy, felt betrayed by the accord. In his view, the pact was a sellout—India was dictating terms on behalf of Colombo without securing a separate Tamil homeland, or Eelam. He saw Rajiv Gandhi’s peacekeeping mission as an occupying force, not a friend.

India’s Military Quagmire

Soon after deployment, the IPKF found itself in an all-out guerrilla war against the LTTE. Jungle ambushes, landmine attacks, and night-time raids became routine. India’s army, ill-prepared for the terrain and the complexity of the conflict, suffered heavily. Over 1,200 Indian soldiers died, with many more injured.

What was supposed to be a peace mission became a drawn-out, bloody conflict that neither India nor Sri Lanka truly controlled.

Back in Delhi, Rajiv Gandhi felt the heat. His vision of India as a regional stabilizer was now seen as overreach. Tamil Nadu’s public opinion turned volatile, with growing anger at Indian troops fighting fellow Tamils. In Sri Lanka, Sinhalese hardliners also grew suspicious of India’s intent.

Rajiv’s gamble had backfired.

Prabhakaran’s Paranoia and the Death Order

As India pulled out of Sri Lanka in 1990 under Prime Minister V.P. Singh, the LTTE celebrated it as a victory. But for Prabhakaran, the threat was not over. He feared that Rajiv Gandhi’s return to power—then widely anticipated—would mean a renewed military offensive against the Tamil Tigers.

According to former LTTE insiders and subsequent investigations, Prabhakaran made a chilling decision: Rajiv Gandhi had to be eliminated.

The LTTE’s intelligence wing, headed by Pottu Amman, began plotting the assassination. A team of operatives trained for a human bomb mission. The plan was bold, symbolic, and devastating.

The Night of May 21, 1991

It was supposed to be an ordinary election rally in Sriperumbudur, just outside Chennai. Rajiv Gandhi, campaigning for a Congress comeback, walked down a pathway, surrounded by supporters and local party workers. Among the crowd was a young woman named Dhanu, posing as a well-wisher with a garland in hand.

As Rajiv leaned forward to greet her, she activated the explosive belt hidden beneath her dress. The blast ripped through the crowd, killing 15 people, including the former Prime Minister. His mutilated body lay on the ground, unrecognizable except for his sneakers and a ring.

India stood stunned. For the second time in less than a decade, the Nehru-Gandhi family had lost a leader to political violence.

A Turning Point for the LTTE and India

The assassination of Rajiv Gandhi triggered a swift and permanent shift in India’s approach. The LTTE was banned as a terrorist organization. Indian security agencies launched a coordinated crackdown, both within India and in cooperation with international agencies.

Over time, several conspirators were arrested and sentenced. Some spent decades in prison; others died mysteriously. The woman who carried the bomb, Dhanu, became the first suicide bomber on Indian soil—a gruesome legacy that would inspire future terror groups across South Asia.

Public sympathy for the LTTE vanished overnight. In Tamil Nadu, where many once viewed the Tigers as freedom fighters, there was widespread shock and condemnation. Even hardline Tamil politicians distanced themselves from Prabhakaran’s actions.

The End of the Tiger

Prabhakaran himself remained elusive for nearly two more decades, building a shadow government in Sri Lanka’s northern provinces and ruling with an iron fist. But the tides turned in the late 2000s.

In May 2009, the Sri Lankan army launched a final offensive. Prabhakaran, along with his son and senior commanders, was killed in Mullaitivu. The LTTE, once among the world’s most formidable insurgent groups, was dismantled.

For India, the death of Prabhakaran was not a moment of celebration—it was the closing chapter of a long, painful relationship filled with missteps, bloodshed, and a sense of what could have been.

Legacy of a Tragic Alliance

The brief interaction between Rajiv Gandhi and Prabhakaran in 1987 remains one of modern history’s most ironic moments. Rajiv’s offer of a bulletproof vest, made in good faith, stands today as a haunting metaphor—an olive branch offered to the very hand that would later take his life.

Their relationship encapsulates a broader truth of South Asian politics: that alliances are often transactional, trust is fragile, and ideological movements can quickly spiral into vengeance.

For India, the Sri Lankan misadventure remains a cautionary tale of overreach without ground intelligence. For Sri Lanka, it is a reminder of the price of ignoring minority grievances. And for Prabhakaran, history will remember him not as a liberator, but as the man who killed one of India’s youngest leaders.